Timmy Irani, Mathew Zefeldt, Debbi Kenote

International Residency 2022

Timmy, Mathew and Debbi joined us in collaboration with Cob. Gallery

THE ARTISTS

DK: I did my undergrad in painting and installation, and my Masters in sculpture. While at grad school, I found myself making three-dimensional paintings, or thinking about my sculpture work as three-dimensional paintings. When I graduated, I started painting again, but this time I wanted to use acrylic instead of oil. I also started art handling. This gave me a perspective on what makes a good structure for a painting. And as I worked, I became interested in manipulating that. Most painters think of the work as just on the surface, but through sculpture I think about the form a little more. I think most artists’ visual language comes from early on. I grew up in the Pacific Northwest, in a tiny town, on a small island, surrounded by nature. It was a deeply rural childhood, and I was home-schooled. I didn’t have access to museums and art galleries. I observed nature and others’ interpretations of nature, through illustrations and interpretations of nature through local wood carvers. I grew up on 50 acres. The area is wild. You can’t look through forests because they are so dense. It’s magical. It was a complete ushing of source material. I’m not able to describe the allegorical meaning of that, in the way you would use a lexicon or some kind of language. It’s more intuitive than that. With abstraction, there is a feeling I am trying to get out of a viewer. When I’m moving shapes around, they’re saying something, but not something that can be captured in words.

MZ: Your work has a lot of editing in it. It evolves, even if you use an initial drawing. That’s something that has been exciting about being next to you: seeing that intuitive process and careful looking.

DK: I do it old school. I paint everything as a whole, by hand. I’m trying to use less colour because I love colour. When something isn’t quite working, rather than look at a colour theory book on a Master Renaissance painter, I’ll refer to my previous work to see how I solved it before.

MZ: I fell in love with painting at college. A lot of my references are 1960s art history: Pop Art, like James Rosenquist, photorealism, and a slightly colder approach to painting that occurred post-Abstract Expressionism. Gerhard Richter posited his painting practice as an extension of the photographic process. From camera, to dark room, to canvas, to paint. I am trying to apply some of these ideas to video games. They are huge within our day-to-day lives, and yet are not explored within contemporary art. Right now, I am painting exclusively from Grand Theft Auto. I’m trying to think of myself as a virtual en plein air painter or virtual Impressionist. The paintings are a kind of worm hole between the digital and physical worlds. I’m drawn to GTA because it parallels our own so strongly. It’s a place that feels familiar and because of that, uncanny. While I play the game, I am playing a near identical avatar of myself, which I have curated. There is endless customisation and self-expression through consumerism – another eery parallel with out world. I misplay the game. I will do repetitive actions, like driving my car off a cliff twenty times in order to capture the right angle for a painting. I also might do a virtual nature hike, which feels more peaceful and meditative. It’s amazing how much there is to do in the game – to position yourself as an artist, making images exclusively from that game. I found it’s always helpful have these parameters in creative practice. You can’t just to anything, it’s helpful to have set rules for yourself. This game has been that.

TI: I studied architecture at college, and after that worked in Tech for a little bit, doing UX design. Growing up, I was always a major doodler, but I didn’t pick up paints for a long time. I got into art because I saw some that I wanted, but I couldn’t afford it, so I started making paintings for my room. My work has a built quality to it. There’s a lot of wood, which comes from my architecture background. The way I paint flat paintings also has a built method, where often I do more cutting than painting. I use the same software I used in school for architectural drawings. What bothered me about architecture were the physical limitations – you have a budge, you have to be realistic. Whereas in my artwork, I can go crazy. The aesthetic comes from my obsession with the digital realm. I was a big computer gamer, like Mathew. I lived in these worlds for a long time as a kid and into early college.

MZ: I was thinking, during this conversation, that all three of us are concerned with what worlds we want to be in through our art.

TI: It’s definitely an escape for me.

THE WORK

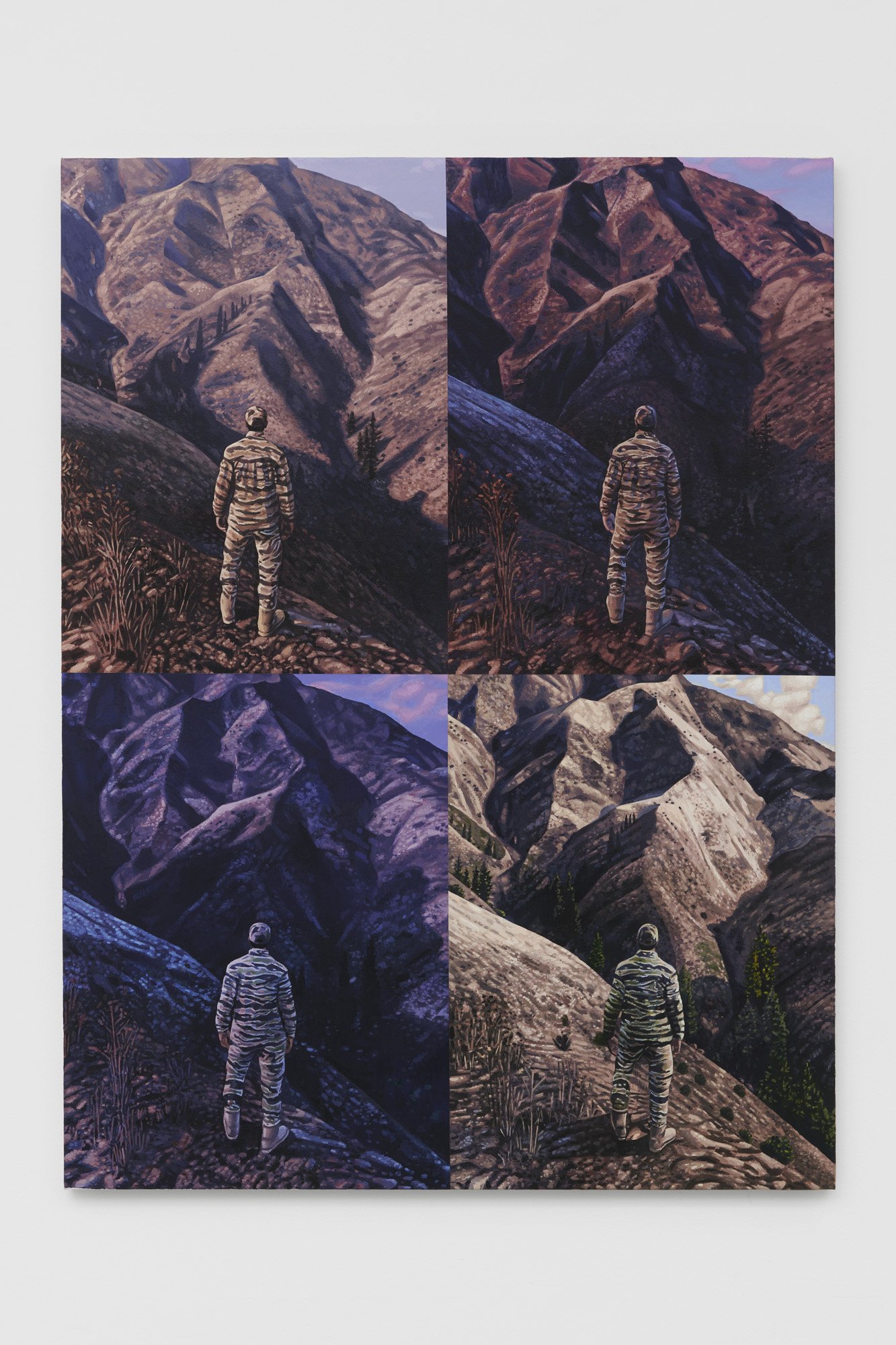

MZ: This work Blending In, is from a vista in Grand Theft Auto. I grew up at the base of Mount Diablo in the Bay Area, and there’s something about this image that reminds me of that. I gave myself the parameter of trying to stand in the same place for an extended period of time, watching the light change. 24 hours is the equivalent of 48 minutes in the game – every 48 minutes there’s a sunrise, a sunset, a noon. I divided that timeframe into four, taking screenshots every few minutes. Here, there are four images that relate to four different kinds of light. There’s a Caspar David Friedrich reference of a third person viewpoint of a vista. There’s also Monet’s Haystacks – I am looking at the same object in different lights and studying how light changes colour, but through a digital lens. Also, I’m wearing camouflage, which isn’t something I wear in real life but is something I feel I can wear in the game – I am interested in assimilating into that world through camouflage. This becomes a metaphor for everything being made of the same material: everything in the game is a polygon, just like everything in our world is an atom. And everything in the painting is paint. It’s all the same stuff but just different recipes or amounts.

DK: This is called A Mountain Could Be a Diamond, the second in a series. It is a playful title, one that speaks to the idea of potential and growth. This relates back to natural forms and childhood. I think about how we interact with the world around us as children, through play and make-believe. I’m interested in how imagination is something we consciously put away and make less of a priority as we age. But what if we revert to that way of thinking? A shape can be anything. A diamond is a heavy-handed object within society, but really, it’s just a rock. This painting is called Many Moons, and it’s a good examples of something I do often, which is to take an image and flatten it. Both include the same tree shape, but in Many Moons, I have switched the palette and reframed the image. Whereas in A Mountain Could Be A Diamond it holds its form. It goes back to this idea that anything can be anything, it’s all how you see it. Mathew and I share rules: using our canvases like filters. Tim and I share a graphic style, choosing a shape and cutting it out in space. All three of us tap into a kind of nostalgia for things that happened before we can remember. Colours that were popular during our childhood or scenes from movies. They all sit in our peripheral vision. The nostalgia they feel for video games is what I feel, for an isolated childhood in nature.

TI: I wanted to do something site specific to London, incorporating an American’s view of coming to London for the first time, bringing things that I view as quintessentially British. As well as things I like and have observed from walking around here. For example, the barricades, cones and road signs, which are colourful and plastic. They remind me of playmobile toys as a kid. Lately it’s been very windy, so the barricades are toppled over everywhere. They don’t do anything. They’re hazards. Then there are pansies – I saw a lone one in someone’s front yard, and it stood out to me. This one is called Fish and Chips. The puffer fish comes from a previous work, I’ve shoved the chips in its mouth, like a bouquet. It’s under a willow tree and the fish is in a Camden rubbish bin, with the Camden logo. I’m straightforward with the names because I work with these objects so much that I become familiar with them, thinking that everybody knows what they are, but it’s not that obvious. I paint by hand, using the exacto plane. I tape over and I cut out all the shapes, pretty much one by one. A lot of them are tiny. I try to get rid of most of the human imperfections but if they were all gone the work would just look like it’s printed.

THE RESIDENCY

TI: We’ve made connections that will go further than here.

MZ: We’re West Coast, Midwest, and East Coast. So we cover the US. It will be nice to reconnect after this.

DK: It’s been so productive. I’ve enjoyed seeing other people’s ways of working. we’ve all been able to talk about things in the art world that are challenging that you don’t get to talk about freely often. Like pricing. Locations. Efficient ways of painting. Other artists that we’re interested in.

MZ: It’s been cool sharing the space. That’s something I haven’t done since being in school. Here, having someone nearby, who you can grab to get a second set of eyes on work has been great. Being a painter can be isolating. You often just go to your studio, close the door, and put your headphones on. It’s been amazing being able to be creative and productive, around others, feeding off each other’s creative energy. I think all of us realised in the first week that we are workaholics.

TI: I wouldn’t even say we push each other to work harder, it’s more we work hard, together, in solidarity. I have a pretty big studio now but I started making art out of my room, which is smaller than this.

MZ: It’s another parameter. You have to find a way to be creative within it.